Fly Dresser Peter Simonson's Happy Obsession with Streamer Legend Carrie G. Stevens

His Flies Are Almost Too Beautiful to Fish

Peter Simonson’s streamers are so beautiful that it would be a shame to tie one onto a leader and swing it through the bottom of a pool. If you did that, a brown trout might attack it and ruin it. And then what would you have?

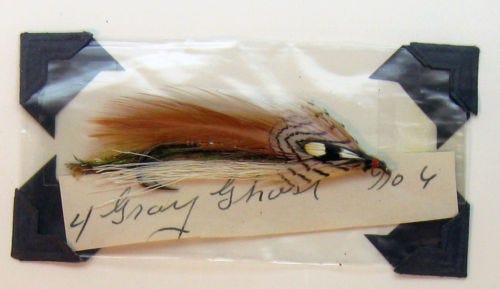

Simonson, who calls himself a “fly dresser,” mostly sells his streamers to collectors at fishing shows for $25 each. That includes a small padded display case similar to the ones you see holding Mickey Mantle rookie cards.

His flies all follow the patterns and recipes established by the late Carrie G. Stevens, who in 1925 became an overnight fly fishing sensation with a fly that later evolved into the Gray Ghost, one of the most famous streamers ever tied.

Mr. Simonson lives just a few hours from the Maine region where Ms. Stevens once lived. He’s a retired electrical engineer who once worked in the defense industry doing “signal processing systems”, whatever that means. “Math intensive stuff,” he explained.

Simonson loves the Carrie Stevens flies because they’re beautiful and because they’re little marvels of feathered engineering. “A Gray Ghost works,” he said. “If they’re tied right, they swim like a bait fish. They stay upright in the water. And the wing will move side to side like the tail of a baitfish.”

It’s easy to see how the story of Stevens’ meteoric rise from an occasional bait angler to the pantheon of fly tying legends would be appealing, especially for a New England angler like Simonson.

Carrie Gertude Wills was a hat maker when she married Wallace Clinton Stevens and moved to the Rangeley region of Maine near the Upper Dam that helps form Mooselookmeguntic Lake. Her husband was a fishing guide working in the Androscoggin River watershed. That meant guiding on the Rangeley and Kennebago Rivers and the surrounding lakes.

Reading about her, you get the sense that Carrie Stevens didn’t fish much at all until, almost overnight, she was suddenly a nationally famous fly angler thanks to Field and Stream Magazine. The story goes that she tied her first fly at the urging of one of her husband’s clients, Charles “Shang” Wheeler. Wheeler was a Connecticut state senator, outdoorsman and artist whose hand-carved duck decoys today can sell at auction for more than $50,000.

So at Wheeler’s suggestion, on July 1, 1924, Stevens tied some gray feathers to a hook. She was trying to imitate a key baitfish of the area – a rainbow smelt. Even without the benefit of a vise, tying the fly couldn’t have been too hard for a woman who, as a former milliner, knew how to work with her hands. That first fly would later be dubbed “Shang’s Go Getum.” And after that, with a few adjustments, it likely became one of the most famous streamer patterns of all time, the “Gray Ghost.”

But all that happened later. On July 1, 1924, Carrie Stevens just wanted to see if her first fly might actually fool a fish. So she marched to the nearby Upper Dam pool with one of her husband’s split cane fly rods. And damned if she didn’t start catching fish, both trout and salmon.

Then she hooked the fish that would change her and her husband’s life. After an hour-long battle, Stevens landed a brook trout that weighed 6 pounds 13 ounces and measured 24 and three quarters inches. That was good enough for second place in Field and Stream’s annual fishing contest.

But that still wasn’t enough to make her famous. The next year the magazine published her account of the catch. She wrote “He was caught with a Thomas rod, nine feet in length, a Hardy reel, an ideal line, and a fly I made myself.”

That last turn of phrase – “A fly I made myself” – was the bit that launched her fly tying career and eventually led to fly tyers like Peter Simonson falling in love with her innovative and gorgeous streamers.

Thanks to Field and Stream, Carrie Stevens and her husband were suddenly at the center of the fly fishing world. His guide business grew quickly and her fly tying business went crazy. She started selling her flies for a dollar each. That’s about $17 a tie in today’s dollars. She put up a sign in front of her home that read “Carrie G. Stevens Maker of Rangely Favorite Trout and Salmon Flies.” She also sold her flies through local fly shops.

Ms. Stevens turned out to be a savvy marketer. She abandoned the common practice of numbering her flies and quickly started coming up with clever names. There was the Rangeley Favorite, the Stevens Favorite, the Pirate, the Green Beauty, the Wizard, the Golden Witch, the Blue Devil, the Greyhound, the Happy Garrison, the White Devil, and the Don's Delight.

During WWII, she even produced a “Patriotic Series” of flies tied with red, white and blue heads. She named them The America, the Casablanca, The General MacArthur, and Victory.

But Carrie Stevens was more than just a shrewd marketer. She also innovated with longer hookshanks, fly shoulders to imitate gill plates, and different materials designed to make the fly look more authentic.

Meanwhile, Peter Simonson has evolved into something of a Carrie Stevens fly tying historian and sleuth. He grew up spin fishing for sunfish, perch and bass in the Croton River, in Westchester, NY. After moving with his wife to Greenville, NH in the early 1980s, he started fly fishing in 1996 and soon was tying flies with the help of “Talleur’s Basic Fly Tying” by Richard Talleur.

Before long Simonson found Carrie Stevens’s flies. “They were very pretty,” he said. “There’s something about them. They look like they're alive. They have the fluid motion that a baitfish has.”

He studied fly tying under Mike Martinek, another New England guru who published two books of his own flies that were tied in the Carrie Stevens style.

Then Simonson started trying to tie all the flies documented in the book “Carrie G. Stevens: Maker of Rangeley Favorite Trout and Salmon Flies” by Graydon and Leslie Hilyard (It’s still available on Amazon for $57.43).

But then he wanted more, he said. “The more I digged, the more I found.” He started writing letters to the directors of fly fishing museums trying to find any undocumented Stevens flies. Donald Palmer, the director and founder of the Outdoor Sporting Heritage Museum, in Rangely, Me. gave him access to the museum’s large Carrie Stevens collection. “I was like a kid in a candy shop,” Simonson said. “He even let me touch the flies.”

Simonson has documented 179 different Carrie Stevens flies that had not been previously identified in the Hilyard book. Last year he was featured in Fly Tyer Magazine. He also has a database with all the recipes and you can view his work at his website at www.petersimonsonflydresser.com

As obsessed he is with documenting and tying the flies, he also loves to fish them. In the fall, Simonson likes to drive up to the Connecticut River near the “First Connecticut Lake” just across the New Hampshire-Maine border, not far from the Rangeley region where Carrie Stevens lived.

It’s a quiet area that gets little fishing pressure, even when the salmon run up the tributaries in the fall. “You sort of get to pretend that you’re that old rugged outdoorsman,” he said. “It’s this old heritage style of fishing.”

When he finds a quiet pool, he said, “I’ll put on a Gray Ghost and swing it through and see who’s there.”